Serum Institute Of India Takes A Multipronged Approach In Quest To Produce World’s First Covid-19 Vaccines

Avinash Gowariker

By Manu Balachandran and Naazneen Karmali

When the coronavirus pandemic broke out earlier this year, Adar Poonawalla, CEO of Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest vaccine maker by number of doses produced and sold, weighed the options: “Do absolutely nothing and watch how it unfolds, or take the risk and become a front-runner.”

The 39-year-old chose the latter and went on a dealmaking frenzy, which has put the privately held firm in the forefront of the global race to develop a Covid-19 vaccine, he says in a telephone interview in late September from the company’s Pune headquarters, the latest of two interviews for this article. His father Cyrus Poonawalla, worth $11.5 billion, founded the Serum Institute in 1966 and remains its chairman.

“It’s a huge personal risk I am taking,” says Poonawalla. The firm, he says, is investing $800 million to help find, and then produce, a vaccine, and has already spent $300 million of that.

To beat the virus, Serum Institute has secured five partnerships over the past six months; the biggest is its deal with AstraZeneca. In June, the UK pharma giant licensed Serum Institute to manufacture a billion doses of a potential Covid-19 vaccine called AZD1222—with 400 million to be delivered this year. For comparison, Serum Institute’s annual output now is over 1.5 billion doses.

Serum Institute’s deal with AstraZeneca likely involves an upfront payment based on the expected number of doses needed, says a company insider who asked to be unnamed. The scale-up to produce them is a major financial commitment. “I decided to sacrifice three of my existing facilities, which make some very lucrative vaccines,” Poonawalla says. That opportunity cost, Poonawalla reckons, could total millions of dollars. “I am afraid to even calculate that figure,” he says. “But again, I’m only accountable to myself.”

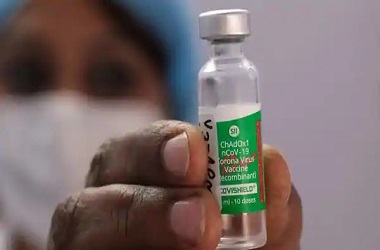

The vaccine is based on a genetically modified version of a common cold virus that infects chimpanzees, and was first developed by researchers at the University of Oxford, with AstraZeneca signing on to distribute it. “We are the only one [in India] who have the [manufacturing] capability,” Poonawalla says. Half the doses are planned for India, which will be marketed under the brand Covishield, and the other half are earmarked for the rest of the world, in particular developing countries.

AstraZeneca launched advanced clinical trials for tens of thousands in Brazil, South Africa, the U.K. and the U.S., while Serum Institute started its own trials with 1,600 volunteers across India and dedicated three of its facilities to begin production of more than 60 million doses monthly of the vaccine—with plans to ramp up to 100 million doses by December. Trials in several countries, including India, were briefly halted, then resumed, after an unexplained illness in one patient in a U.K. trial in early September.

“Vaccine production is like a rollercoaster ride with all sorts of probable results; you just need to be patient until the final result is out.”

“We could have launched the vaccine early next year if the trials hadn’t been stopped. That has really put a wrench into the works,” says Poonawalla, estimating the trials could now extend to January. “We’re trying everything we can to make up for lost time.”

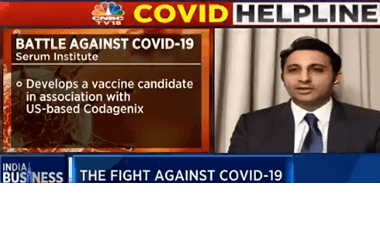

He’s also hedged his bets by developing other Covid-19 vaccines. “We are working with multiple partners across the U.S., U.K. and Europe on four different vaccine candidates,” he says. “We never assumed that only one vaccine candidate would work. Vaccine production is like a rollercoaster ride with all sorts of probable results; you just need to be patient until the final result is out.”

In February, Serum Institute teamed with Codagenix, a clinical-stage biotech company in New York, to codevelop a single-dose intranasal Covid-19 vaccine that removes the virus’ harmful properties while keeping the antigens. Serum has since secured Indian regulatory approval to manufacture it. Meanwhile, work is underway with global pharma giant Merck to codevelop a vaccine by modifying a measles virus vector to carry coronavirus antigens.

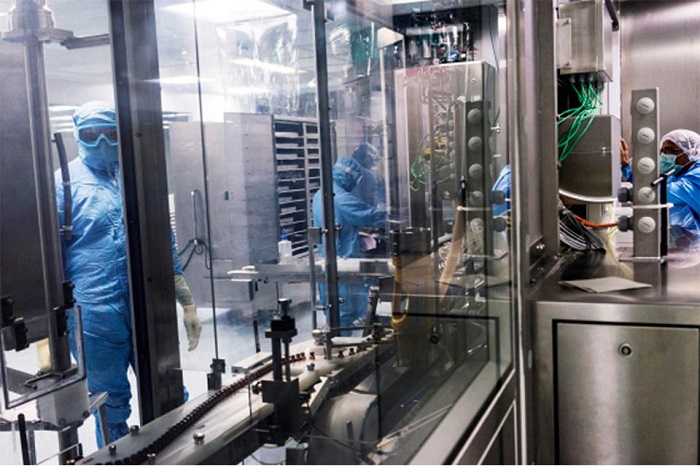

Poonawalla inside a vaccine-making unit at the Serum Institute of India. Avinash Gowariker

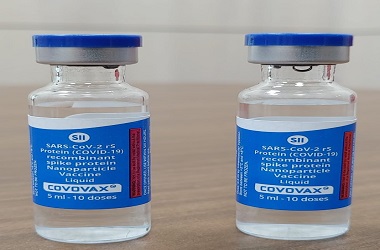

For these two vaccine candidates, “we’re codeveloping, scaling it up and doing the trials ourselves,” he says. In September, the company inked another deal with U.S. pharma firm Novavax to develop and commercialize its Covid-19 vaccine candidate NVX-CoV2373 in low- and middle-income countries, including India. Serum Institute aims to deliver a billion doses of NVX-CoV2373 by 2021. “Along with these, we are working on two of our own candidates, which we hope should be available towards the end of 2021,” he says.

“The only lesson we have learned from this epidemic is how underprepared we were in manufacturing, in our health systems, detection and testing.”

To support all these initiatives, Poonawalla has set up and chairs a new company, Serum Institute Life Sciences, that is building a $300 million, first-of-its kind “pandemic-level” manufacturing facility in Pune, including research and development labs. It will be capable of producing 1 billion vaccine doses when it opens two years hence. He believes the world will likely see another pandemic in the next few decades. “That [next] pandemic could be even worse and deadlier than Covid-19,” he says. “The only lesson we have learned from this epidemic is how underprepared we were in manufacturing, in our health systems, detection and testing.”

In Serum Institute’s home market of India, a vaccine is sorely needed. India has more than 6 million Covid-19 cases—putting it second worldwide in cases behind the U.S.—and more than 100,000 related deaths. The pandemic is more than a healthcare crisis—the Indian economy saw a 24% contraction year-on-year in the quarter ending in June, due in part to nationwide lockdowns in April and May.

Serum Institute is also looking beyond vaccines. In April, the company partnered with Pune-based molecular diagnostics firm Mylab Discovery Solutions to expand production of its Covid-19 testing kits. “We kept thinking about what we could do to help open up the economy, because a vaccine may or may not come, even after a year,” says Poonawalla.

Working with multiple partners has other benefits: Even if only one vaccine candidate proves successful, Serum Institute and its partners can springboard off it to produce more effective variants. When a vaccine is finally found, demand from governments should be huge. “Governments will want to vaccinate their whole population, and stockpile,” says Poonawalla.

Setting up these partnerships is a calculated move, says Anurag Rathore, a professor of chemical engineering at Indian Institute of Technology Delhi (IIT) and a scientific advisor to several biotech companies. “Historically, companies that were the first to bring out a medicine have always had an advantage, even if a second drug was of better quality,” he says. At the same time, “the challenge is to capitalize on the gains, and that means manufacturing at risk to start selling the drugs as and when the trials are over. In that sense, Serum Institute’s call is a commercial decision, a bet that is like any other, which could go either way,” he says.

Avinash Gowariker

“At this moment, we can simply hope that Serum Institute can deliver, and we are eagerly looking for an escape from the situation,” says Arokiaswamy Velumani, chairman of Thyrocare Technologies, one of India’s largest private testing laboratories.

The Poonawallas have been fierce advocates of increasing global access to immunizations, and their company is a key supplier of vaccines to the developing world. In September, Serum Institute clinched a $600 million deal to supply 200 million doses of Covid-19 vaccines at $3 per dose to the global vaccine alliance Gavi and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for distribution in India and low- and middle-income countries. The Gates foundation will provide a total of $300 million to Serum Institute as an advance. “I see the next decade as the golden years for the vaccines industry worldwide,” says Poonawalla.

It will be up to the government to decide on how best to distribute nationwide an estimated 2.8 billion doses (it’s a two-dose vaccine), Poonawalla says, but he hopes the government will cover the costs. “We are not asking for any money for dedicating a manufacturing plant, including the manpower, energy cost, and other things, from the government. All we are saying is, buy the vaccine and give it free to everyone so that no citizen of India has to pay for a Covid-19 vaccine,” he says.

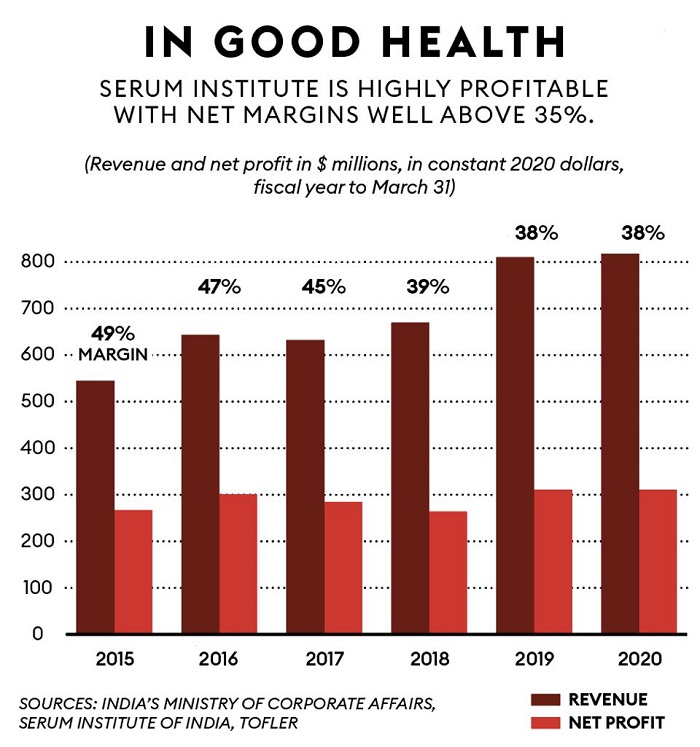

For more than five decades, his father Cyrus built this business empire on the back of affordable vaccines, which helped Serum Institute penetrate the export market without large-scale promotions or marketing. The company, which had $804 million in revenue in its latest fiscal year, estimates that about 65% of the world’s children have received at least one of its vaccines. Cyrus started the company with a small factory on the family’s stud farm.

Technicians monitor vaccine vials passing through a filling and capping machine at a Serum Institute plant in Pune. Sanjit Das/Bloomberg

Back then, the farm’s retired horses were donated to the government-owned Haffkine Institute in Mumbai, which made vaccines from horse serum. With locally produced vaccines in short supply in India and imports commanding high prices, Cyrus saw an opportunity and launched Serum Institute. In 1974, it introduced a diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) vaccine for children, a serum for snakebites in 1981 and a measles vaccine in 1989. By the following year it was the country’s largest vaccine manufacturer, and obtained accreditation from the World Health Organization. That accreditation “meant we could export our products and sell in other countries,” says Poonawalla, who joined the family business in 2001 and became a director five years later. “That was the real turning point.”

In 2012, Serum Institute bought Dutch vaccine maker Bilthoven Biologicals—its first international acquisition. With it came the technology to make an injectable polio vaccine, which then was available from only three producers globally. Five years later it bought Czech Republic-based firm Nanotherapeutics for $81.4 million and increased its production capacity fourfold. This business was sold in May for $167 million to Novavax.

“We’re in 170 countries globally now. Until the [Indian Prime Minister] Narendra Modi government came to power and started buying a lot of vaccines, exports contributed 85% of our total sales. Now it’s about 60% exports and 40% local sales,” Poonawalla says. Despite pandemic- led disruptions this year, the company is still on track to launch a new dengue drug in addition to a vaccine for malaria two years hence, he adds.

Cyrus Poonawalla founded the privately held Serum Institute in 1966. Sanjit Das/Bloomberg

But over the next few months, Poonawalla warns production costs will rise. “With the extremely high GMP [good manufacturing practice] costs and regulations, we may have to slowly start increasing prices of vaccines.” To mitigate the increase, he expects the Indian government to allocate more money to the healthcare sector. Between its Covid-19 partnerships, ongoing development of key vaccines and the firm’s foray into testing kits and newer areas of business, Poonawalla has his hands full. “I don’t imagine myself expanding in a major way, or diversifying in anything else,” he says.

Going forward, Poonawalla sees the firm leading the industry. “The significance of what Serum Institute does—and what other vaccine manufacturers do—has always been understated and underplayed. Vaccines aren’t recognized or spoken about like automobiles or the consumer sector,” he says. “But, people have now realized how critical vaccine manufacturing and research really is to humanity.”

This article was adapted from Forbes India, a licensee edition of Forbes Media.

Updated:An earlier version of this article stated that the Serum Institute of India hoped to cap the price of the Covid-19 vaccine in India at $3, but the price, in fact, still needs to be determined.

What Might Have Been

Serum Institute has been privately held by the Poonawallas from its start, but over the years, Poonawalla and his father Cyrus have been wooed to go public. One episode came five years ago when the family was in talks to sell 10% of the company, then estimated to be worth $12 billion. The deal that would have been India’s largest-ever private equity investment by value.

“We had looked at a stake sale because people said, ‘You’ve got so much value in your company, why don’t you unlock a little bit of that and use it to acquire technologies or other companies,’” says Poonawalla. “We then said ‘forget it.’” In hindsight, Poonawalla is glad about the decision. A sale, he says, would have eventually forced the firm to go public, and diluted the family’s control over the company. “If we were a listed company, I would have to be accountable to shareholders, investors and bankers,” he says.

Poonawalla now says that he may take outside investments for the new Serum Institute Life Sciences company. “I may consider raising private equity funds if I can get a valuation of around $8 billion [for it],” he says.

Source - Forbes